Interview

Project CW

Interview

Project CW

Interview

Project CW

Interview

Project CW

Interview

Project CW

Created:

15 October 2024

Contributors:

Zakhar

Artem

Nata

Barys

Hanna

Aleksandr

Alex

Created:

15 October 2024

Contributors:

Zakhar

Artem

Nata

Barys

Hanna

Aleksandr

Alex

Created:

15 October 2024

Contributors:

Zakhar

Artem

Nata

Barys

Hanna

Aleksandr

Alex

↑

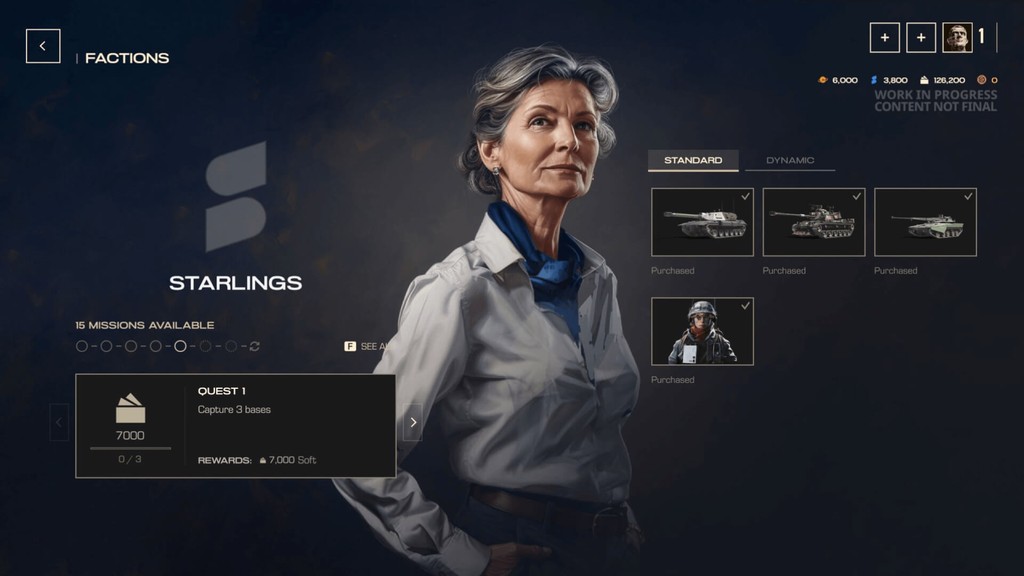

Basics of the game’s Factions

Artem: Andrey Beletsky, Slava Makarov and Anton Pankov were discussing the development of Tanks and it became clear that the American market for Tanks was underperforming. The Americans had their own approach to gaming and their own demands, which were very different from the market in the CIS region, which was more profitable. Meanwhile, there were also Asian countries with their own specific preferences. It turned out that if you took the Tank tree, the left side would be more appealing to Asia, a part where the veterans fought would interest the CIS and some very small or non-existent piece would appeal to America. This is when the idea came up to scale the team and start experimenting with different products.

The idea for a story-based game for Warhammer emerged but was scrapped with the comment: "We don't have the expertise for that." How could they gain that expertise if they didn't try such projects? Another aspect was that long-time employees of the Tank project were getting tired and were considering leaving, which also put pressure on management.

There is a Facebook at Work talk from Minsk in 2018 where Anton, Andrey and Slava talked about the idea of a TLC for World of Tanks, based on the Cold War and modern Tanks. The core idea was to make the gameplay more dynamic, with a different part of the core, but as a continuation of World of Tanks. I don’t know what happened later. The console version of Tanks either faced external pressure or copied the idea themselves, but they decided to lead the way and developed something called Cold War. They made a big mistake from the product standpoint. There is a theory that they were pressured: they wanted to release a second game but instead created a second product within the same game, splitting the core audience. This didn't just shoot them in the foot, but in the left lung — by splitting their core, they are still suffering.

Meanwhile, until 2018, there was another initiative called Excalibur. The videos and interfaces were created by Sergey Borisovich and his team in Seattle. What happened there is unclear, but the gameplay was similarly slow, only the doctrine of war changed: armored fronts, machines had infantry, restrained military abilities, but it still resembled World of Tanks. For some reason, this product never made it out of pre-production.

Then, from 2020 onwards, we participated in World of Tanks Cold War for the American market. This was classical Tanks. The only difference was how the vehicles were assembled. In 2022, we put together prototypes on a new engine and started testing them in America. After these tests, everything began to change significantly as we received feedback from the audience. The combat lacked dynamics, and it wasn’t engaging to assemble the machines. More specifically, it wasn’t fun to mutate the same platform into different roles. For example, you had the body of one machine and you could assemble a knight, an assassin or an archer from it. The mechanics seemed overly complicated for the American audience. From there, the idea of pre-assembled heroes emerged — vehicles with special abilities, as this was the "fun" element for them. Everything before that wasn’t fun: assembling and preparation of the characters…

Introduction

Development History of the Game. Previous Products. Timeline.

Introduction

Development History of the Game. Previous Products. Timeline.

↑

Basics of the game’s Factions

↑

Basics of the game’s Factions

↑

Basics of the game’s Factions

Artem: Andrey Beletsky, Slava Makarov and Anton Pankov were discussing the development of Tanks and it became clear that the American market for Tanks was underperforming. The Americans had their own approach to gaming and their own demands, which were very different from the market in the CIS region, which was more profitable. Meanwhile, there were also Asian countries with their own specific preferences. It turned out that if you took the Tank tree, the left side would be more appealing to Asia, a part where the veterans fought would interest the CIS and some very small or non-existent piece would appeal to America. This is when the idea came up to scale the team and start experimenting with different products.

The idea for a story-based game for Warhammer emerged but was scrapped with the comment: "We don't have the expertise for that." How could they gain that expertise if they didn't try such projects? Another aspect was that long-time employees of the Tank project were getting tired and were considering leaving, which also put pressure on management.

There is a Facebook at Work talk from Minsk in 2018 where Anton, Andrey and Slava talked about the idea of a TLC for World of Tanks, based on the Cold War and modern Tanks. The core idea was to make the gameplay more dynamic, with a different part of the core, but as a continuation of World of Tanks. I don’t know what happened later. The console version of Tanks either faced external pressure or copied the idea themselves, but they decided to lead the way and developed something called Cold War. They made a big mistake from the product standpoint. There is a theory that they were pressured: they wanted to release a second game but instead created a second product within the same game, splitting the core audience. This didn't just shoot them in the foot, but in the left lung — by splitting their core, they are still suffering.

Meanwhile, until 2018, there was another initiative called Excalibur. The videos and interfaces were created by Sergey Borisovich and his team in Seattle. What happened there is unclear, but the gameplay was similarly slow, only the doctrine of war changed: armored fronts, machines had infantry, restrained military abilities, but it still resembled World of Tanks. For some reason, this product never made it out of pre-production.

Then, from 2020 onwards, we participated in World of Tanks Cold War for the American market. This was classical Tanks. The only difference was how the vehicles were assembled. In 2022, we put together prototypes on a new engine and started testing them in America. After these tests, everything began to change significantly as we received feedback from the audience. The combat lacked dynamics, and it wasn’t engaging to assemble the machines. More specifically, it wasn’t fun to mutate the same platform into different roles. For example, you had the body of one machine and you could assemble a knight, an assassin or an archer from it. The mechanics seemed overly complicated for the American audience. From there, the idea of pre-assembled heroes emerged — vehicles with special abilities, as this was the "fun" element for them. Everything before that wasn’t fun: assembling and preparation of the characters…

Chapter 1

Team Structure. Key Figures

↑

Meet the Agents

↑

Meet the Agents

↑

Meet the Agents

Zakhar: Can you tell us about the development team? Are there any stars?

Artem: The team currently consists of 150 people. Around 10 are based in Chicago, where they work on Modern Armor and help with consoles. There are 52 people in the Serbian office — individuals with experience working at Ubisoft and in large-scale productions, although they lack experience in releases and making complete games. For us, they are the "young blood." Then there's the core team, which survived the relocation from Minsk, comprising about 50 people, more than half of whom work in art, and 80% are former World of Tanks employees.

Among the stars is Danya Parashchyn, also known as "Murazor." He used to be a streamer, once shook hands with Viktor and criticized Rubicon as a failure. For his critique, he was told, "If you think it's bad, go and fix it." Now, he's in charge of Cold War. There are also professionals, veterans with 7–10 years of production experience, such as Misha Litvinskiy, who has always worked on hard surfaces — tanks and other vehicles.

The strongest expertise lies in the engineering department. It's important to understand that our team is building both the engine and the game simultaneously. Bronislav Sviglo oversaw the release of World of Tanks 1.0, and Denis Deshko is the system architect, while Arseny Kravchenko and Artem Brichko are tech artists. These people have been working for a long time and their superpower is making vehicles.

There are also rising stars among programmers, a group of guys who went through Forge in Minsk. Now they show their potential. Like all young people, they think more about opportunities than limitations. Ilya Yakush is one of them. Since 2020, we've also started adding people with completely different expertise to bring new perspectives. On the Game Design team since 2020, only Danila and I remain, the rest are new hires with no experience in Tanks and half of them don’t speak Russian.

You all know Hanna. For much of the team, it was unclear why she was hired as the art director for the product based on her resume. But to create a new product that stands out in the market, you need someone with her experience. The team needed to be reassembled. Deploying the old World of Tanks team wouldn’t have worked to make something fresh and new. In some departments, a third, or even half, and in some cases 80% or more of the creative team had no prior knowledge of the product.

Hanna: Some of them had never worked on games before — some came from marketing. It works well because new people bring fresh ideas. A part of them is lost, but there are the same principles of work, they know how to work under pressure, they know how to work with concepts. We manage to combine nicely because new people give new ideas. Part of the team works on metaphorical concepts, like icons, coming up with completely new approaches, free from template thinking. Everyone says we have the best-looking merch. Alex joined a little over a year ago.

Chapter 2

Team Management Challenges and Project Dynamics

↑

Don’t lose your head over your game’s challenges

↑

Don’t lose your head over your game’s challenges

↑

Don’t lose your head over your game’s challenges

Zakhar: How do you manage the internal collaboration of this big team? How do you build interactions inside the team? How do you decide which ideas to move forward with?

Artem: The preparation period could be divided into different stages, each characterized by its own methods. Right now, methods from previous periods don’t work anymore — they’ve become toxic. When we were preparing the previous builds, including alphas and betas, the team was much smaller and consequently, disciplines were smaller and the communication overhead was minimal. Since we were offline, in one room, on one floor, everything was resolved quickly. And because we were building everything from scratch, the results of each action were immediately visible, which motivated people. All it took was a quick agreement. A startup approach.

It was normal if someone in the team didn’t know what others had agreed upon — you could step in and help your colleague. I would even sit down and do things myself. Now, if I use that method, the team feels terrible because they feel responsibility has been taken away from them. This is a sign of larger-scale production and a bigger team. The dynamic is different now. What stands out is that the older team members haven’t fully adapted to the changes. Especially design, Danila and me - we haven’t adapted. Instead of doing things hands-on, we now need to learn how to delegate. Instead of thinking about how to do something, it’s more about telling someone: "Go think about it and bring me a solution." In some cases, it’s not even about setting a task but providing direction and vision.

Because we are growing from within, many things are changing. We haven’t fully defined our vision and mission. Many things happen from the ground up, which is why I still haven’t been able to explain to Nata for a year now what the conflict at the world level of the game is. One symptom of this situation is onboarding — if you were to join us now, people would tell you: "We don’t have any onboarding. Survive, and we’ll talk in six months." We didn’t even say that. We showed the product, said everything is fine and that we’re heading towards these releases. Maybe it’s not so unusual for the market anymore, as it's coming out of a crisis.

Another challenge is the team’s mindset. Part of it is used to doing things like a New Year’s feature over the course of a year. While this is changing, it's still somewhat present. They have a feeling of security in a corporation. The team doesn’t fully understand the idea of investment and the collective as a living organism. The situation is twofold: they’re building a new product, but even in case of failure, they will still be paid tomorrow. So, the team doesn’t feel responsible; it’s all on management. There’s a dichotomy: the team works with "a stable income," while the management operates like a startup, where funds are limited “daily” according to the milestones. In case of a failure the management gets fired and the team starts working on Tanks 2.

Chapter 3

Failures and How Management Handles Them

↑

Everybody’s dead and there’s a skull grinning in the middle of the screen... but I’m OK!

↑

Everybody’s dead and there’s a skull grinning in the middle of the screen... but I’m OK!

↑

Everybody’s dead and there’s a skull grinning in the middle of the screen... but I’m OK!

Zakhar: Let’s talk about tension points. Has there ever been a time when, after major investments, you had to abandon something?

Artem: Last thing that happened we had to drop the visualization of progression modules on vehicles because the production couldn’t handle it. And that was one of the product’s Unique Selling Points (USP) back in January. I expect some backlash for this. I failed to scale the production properly. This happens on a smaller scale almost every day. Because we are ambitious. Hanna has her maps, I have progression mechanics, Alex has the funnel and Nata has the world bible, a set of mechanics that deliver pieces of the world and narrative to the player.

Nata: The story is being written, but the mechanics are lagging behind. We’re constantly caught in these contradictions.

Zakhar: How do you channel this? How do you dance with what you want and what you can’t achieve?

Nata: In my case, I choose the most prominent point where I can test my hypothesis. For example, I can’t create interactive dialogues with vendors or a cool progression system in the account right now, so I take the battle VOs, which players are likely to hear, that vividly convey the story, and I test a piece of my hypothesis on them. Everything else — will be done at the right time. You focus on one standout point.

Artem: I don’t know, right now I’m not channeling this in any way. I’m in the middle of a desert where the container is overloaded and I don’t have the tools to make use of this conflict. So when the container overflows, something happens — it’s not my action, not the result of my choice. I chose not to choose. For us it’s a bad case right now. For us, there are a few recurring methods right now. One is conflict, often bigger than the actual situation. The second is to just shut up and get things done. Hanna is a good example. Just stop talking. Just take it and start doing it, show the team that this is how it’s going to be. And this strong director’s stance is a good solution right now. The third is explaining why what someone did doesn’t work. This is a cool tool. This is something that’s lacking now. I definitely lack it. To answer Zakhar’s question about how it’s being channeled...

Working on the game's appeal to players.

Barys: Are there moments when the “fun” factor in the game goes down and how do you deal with those moments?

Hanna: Going back to the question: how do you dance? We don’t dance, we run. There’s no sense in thinking about how to do something - we’re fixing things on the go. It’s hard for the team that worked on Tanks because we don’t produce a lot of finished stuff. We’re learning on the go, we make, test and fix on the go. We make a lot, throw it away and we don’t do anything perfectly on the first try. It took a long time to adjust to the idea that we don’t have the intention to make things perfect from the start. This exhausts people a lot. Now we are trying to structure. Around 80% of the work results in negative outcomes, but we have a certain flexibility in our approach.

Barys: It’s a very fine matter - fun. How do you deal with it?

Hanna: It’s a spiral. At first, something works, you dig into it, then all the fun disappears, we push again, come out on a new loop, and you ride it until it breaks again. The third iteration of Meta interface started with a background. We made a cool thing last winter, it looked cohesive, solid and strong. Then, trying new things, we broke it, but from this conflict, a new iteration was born, and by January we’ll put it back together. I see this constantly at the end of production, in design — it breaks, and finally, the structure comes together, and then it starts moving again, little by little.

Artem: The fourth thing that I forgot to add… This team has the freedom to ask for help. You are an example of that. In a very intimate matter, like naming a product. After all, the question is not how to name the product to make more money, but it’s more like: we can’t find the right wording for what we are doing, please help us.

Nata: There were moments when we made something cool, and then it went the wrong way. The same happened with the story. Initially, there was a story with the Cold War, now we have Artem as the vision holder, there’s the American team that was asked to help with cultural sensitivity, and in general, how to make our story engaging for Americans. There’s also work with you. These are the three inputs. My method is to have a check question: when you present each new iteration, how will it fit into the skeleton a year or two after launch? Will this machine keep rolling? Like a show’s engine. And then you look at the story.

PLOT CONFLICT IN THE GAME:

Zakhar: Are there any themes within the game right now that go beyond explosions? For example, the theme of conflict.

Nata: There is a synopsis. This story has a Noland flavor. Everything is very realistic, the stakes are high, but at the same time, some craziness is happening. It’s a metaphor for the Cold War, where you have superpowers and around them, smaller forces branch out. It’s a great standoff, but it’s not built on geopolitics, which we’ve moved away from, but on the conflict between man and machine. This theme is super relevant to everyone who comes into contact with a computer right now. And it will remain relevant. Besides an interesting story, there always has to be a gripping thematic discourse. The player might not realize it, but we plant it there, and for those who find it interesting, they can latch onto it. There are carriers of simple human stories — our characters, whom players can find either relatable or distant.

Zakhar: In the new version of Blitz, we thought of the concept in which characters also appear and they are communicators. You don’t play for them, play as their avatar, so the tone of voice of your game is the tone of voice of all the characters. When you realize that you have characters, each one of them appears and tells what is necessary for the audience. At this point, you have a construct: let this character tell about this update with their tone of voice, accent, music, and phrases. It’s a cool constructivist solution. There’s no Cold War, just the game, but inside, the characters already tell the story.

Nata: We’re trying to bring characters into focus, considering that in battle you don’t see them. You see the machine. In core gameplay, it’s you and the machine. Overall, yes, the tone of the characters and the tone of the game aren’t separate.

PLAYER'S FEELING IN THE GAME:

Zakhar: Do you have a sensory understanding of what players should feel when they enter the game?

Artem: For a newcomer, it’s “make a difference,” curiosity and mighty machines. For someone who has spent ten thousand hours, it’s different, but we still want to preserve that curiosity. The feeling that comes to you a second before you enter the game… The metaphor that came to me is like when there’s tension, and something is happening... like the monkey in 2001: A Space Odyssey touches the monolith — this animal has never touched a polished surface before, it doesn’t exist in nature, but it looks alluring. People have never touched such tanks, but once they do, they can’t stop.

Hanna: It’s an immersion into a strange other world and fun. You come to unwind and there’s the background of a fantasy world.

Nata: Arcade fun, the feeling that you’re welcome here, that this isn’t a game that’s too difficult. It’s fun for me, even if I’m not a super skilled player. It’s like a Caspar David Friedrich painting, where behind the figure, a vast landscape stretches out. That romantic awe of something big opening up before you — that’s the world of our game and the machines. Mighty machines. They exceed your expectations — wow, I can explore all this.

Hanna: I’d also like to add — we’re using modernist architecture. What we use in future concepts isn’t heavily present in the game yet. This curiosity when observing — that’s the aesthetic and educational part. This is my personal desire to create a cohesive, beautiful world based on modernism.

Artem: Returning to the question of channeling. Going back to the feeling of wanting to create something for people helps me get through difficult situations. I would like to have fewer personal conflicts and more creative ones. Creating some kind of entertainment focused on discovery, curiosity with the romanticism of exploration is my anchor when I move away from worries and it’s what I return to. This really helps when there are no rational judgments left.

Zakhar: When you talk about atmosphere, is there a moment when the player gets distracted because they’re drawn into the beauty of the world? Then they find their own places, slowly get to know the game, and interact with it. Or is it more about exploring the equipment — discovering new vehicles, the reason why you’re playing?

Artem: For me, it's a unified product, I am talking about this to the designers. I can’t say I feel this in the product. "I entered the location and was blown away" — I’d love to have that. The last experience I had that’s close to what you're talking about was Space Marine 2, where there’s this view in a window that made me forget I was playing a game. I wish we could grow into a team capable of creating that. Right now, our focus is on mechanics and landmarks on the map. As a team, we can only do what we can do. To make The Last of Us, the team would need to work together for 35 years and go through 10 failures.

NARRATIVE AND STORYLINE IN THE GAME:

Zakhar: We say that the game isn’t narrative, it’s multiplayer, with characters but no plot. However, a storyline often emerges that explains the world’s origins. At the same time, we talk about fantasy, geopolitics, micro conflicts and we don’t specify a geographic location. When Nata talks about conflict, how can we describe the game if there’s no plot?

Nata: You can’t say there’s no plot. There is one, and it develops. There’s a premise. And the conflict on which the world and the heroes are built continues to evolve. We have personal stories for the characters, which will develop over the seasons. There aren’t seasons yet, but they will come. We don’t live in a fantasy world, this is an alternative reality — speculative realism. We try to stay as realistic as possible. We have a world where instead of the Eastern and Western blocs, there are two rival research institutes. Each claims to be saving humanity from all possible threats. One advocates for the safe development of humanity on Earth and the other for space colonization. In reality, they were both created by the same global leaders. They compete without knowing they were born from the same force. Almost every object on the Big Dreams map belongs to one of these two powers. All conflicts are resolved through tanks, as there are rules to prevent escalating war. Force A or B hires agents who clash on the map. Plus, there’s a layer of factions, smaller organizations trying to make their own profit. In the background, there’s a looming threat to humanity, but for now, we’re not focusing too much on it. Our agents in tanks are at the center of the story. It’s a world where progress has triumphed, and global powers abandoned the atomic bomb after something very unpleasant happened during the Trinity test. Nuclear energy developed only for peaceful purposes, and our tanks became the ultimate weapon.

Barys: And how do the game's agents relate to corporations?

Nata: They are hired agents, but if you look closer, some are in it for the money, while others want to uncover who’s behind the global conspiracy. Professionally, they are mercenaries, although we don’t call them that. The dynamic is such that, through the matchmaker, you could end up working for Corporation A or B, you can’t choose. That’s why we say — our agents work wherever they’re called.

Artem: For me, the player never gets a full storyline. They receive puzzle pieces. It’s their task to assemble the pieces. But there are never enough pieces to complete the picture. An example of this is the Souls-like approach: nothing is ever clear. There are only speculations. And yet, you need to give out pieces, because stories sell.

Zakhar: The threat to humanity is the conflict. It exists, it’s existential. From this stems the existential choice: some continue to fight, some give up, some end their lives. But this all outlines the storylines to which applied stories can be attached.

Aleksandr: How strong is the Cold War connection? Yes, it was the peak of tank development, but no conflicts actually happened, and now they all have to be invented from scratch. Why doesn’t the game take place in an alternative present, and how do you justify this retrofuturism?

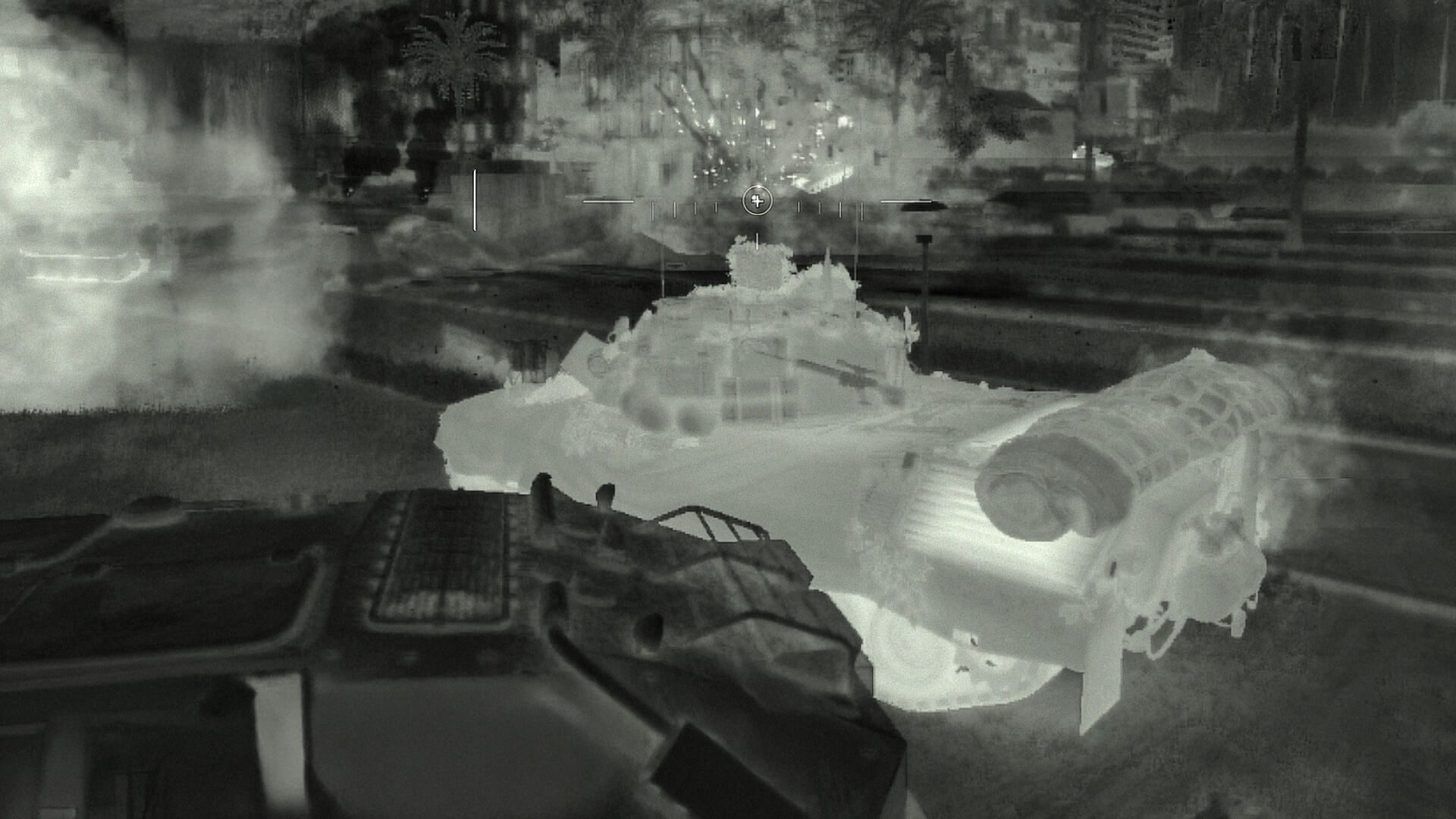

Artem: In the late 2010s the team was thinking about the Cold War period because the doctrine of tank combat had changed, the armor schemes had evolved and there was enough material to avoid breaking the core mechanics of World of Tanks too much and still keep tank battles and the shell vs. armor core mechanic. Because if we talk about the modern period, that mechanic no longer works. There’s a helicopter that can counter a tank and drones that destroy any equipment. Let’s repeat — we don’t have a Cold War; these are remnants of the game's creation history. Drones and helicopters exist, but they are used as abilities by the heroes.

Nata: We aren’t tied to specific years. For instance, the game has women in small shorts which doesn't correspond to any historical period, and everything is mixed from 60s pop culture to the early 2000s. It just gives the feeling that this isn’t happening now.

Artem: We draw inspiration from the aesthetics of different periods, and we’ve discarded historical accuracy as a unique selling point for Tanks.

Nata: The plot doesn’t indicate time or location. Even the buildings resemble real ones but don’t belong to any specific era. We can give some hints if needed.

Aleksandr: Is there a time limit we won’t go beyond, like walking robots, for example?

Artem: Modernity, the war in Ukraine. We need the audience’s trust that a combat vehicle can be illustrated like this in a match. There’s a subjective feeling that it’s a heavy machine, somehow tied to the military. We already have machines that don’t exist: an Abrams chassis with a railgun that’s only been developed for the navy since the 1970s, and it’s so expensive to produce that it’s not used.

The same goes for locations; there were projects for Most Driver, but nothing came of it. However, the technologies are patented or exist in other places. We leave a foundation to prevent the audience from feeling alienated. We can use a location from the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis, place a landmark there to make it believable yet strange. We can put in ships, and the audience familiar with the silhouettes of these ships will understand that it references that period. It’s pointless to talk about this because the game lacks mechanics that would support the theme of the Cold War. This is what we were told in America: you have no associations with the Cold War. No mechanics, no art, no history.

Barys: When the game is multiplayer, there isn’t much opportunity to convey puzzle pieces. Were there any thoughts on how to strategically do this? I mean beyond the game. An example is Overwatch. It’s a multiplayer game and I don’t know much about the characters’ backstories, but there are probably some titles. However, everyone knows about those Overwatch videos with character stories. I got absorbed in that topic and then I began to understand the characters’ histories. Do you have a similar strategy?

Nata: I’ll add about videos and cosmedia storytelling; I advocate for maximizing the story told in the game so that a person who hasn’t seen the videos understands the character of this game. What makes it different from similar ones? We don’t have many similar ones, but I want videos to be provided as needed so that players enter battle for a story and not on youtube.

Alex: We no longer use tank categories; we are moving beyond that. We’ve arcade-ified the gameplay — armor, guns, targeting, static gameplay. You think in different categories here. You consider where you’ll go, and who will support you; this is a different gameplay skill.

UNIQUE GAMEPLAY CHARACTERISTICS.

Zakhar: What will be the unique gameplay feature? What will I feel at my fingertips?

Barys: What must I learn to do in order to win?

Artem: You need to understand your character’s abilities to maximize them. This mindset shifts towards a more utilitarian shooter application. Finding the piano for each hero, knowing the order of each key. In our case, it’s not tanks with abilities. Speaking about Valorant I understood that this is Counterstrike with abilities. In our case this is not Tanks with abilities. Tanks with abilities are Excalibur or Still Hunter mode. Ours is like Call of Duty with tanks. We broke a lot from Current. We only kept the façade of the perception that we have armor, but the mechanics work completely differently from Current.

Aleksandr: What do you think about the term "Hero Shooter," and is it applicable to your game if you consider tanks to be the heroes?

Alex: We have another interesting assumption — when we talk about heroes, we mean a box that holds a tank, and the hero is a person, dual-faceted, which multiplies variability. The tank as a carrier of slow-paced strategic gameplay, which is more forgiving, and as a carrier of gameplay, abilities, etc. The second part is the hero as a person who gives you additional variability for reconfiguration. We’re not exactly a hero shooter; if you had the option to select abilities from different characters, then add MOBA elements with proper purchasing, where you know the order of button presses while seeing who is in front of you, whether you’re under a tower or in the woods. We’re not a hero shooter; we’re not Over. It’s not that hardcore; our base tank carries legacy: we removed armor, the three-caliber rule and some other things, but we retained the core mechanic — how you drive, how you navigate, how you position yourself and how you shoot. However, the movement pattern is different; it remains in the base and sets this vector. Therefore, in terms of sensation and perception, it’s not a hero shooter because the perception of a hero shooter is solely through a person, TPS, PPS — it doesn’t matter. Conceptually, we have a sandbox, and you think in terms of tanks, which involves knowing the locations. We also add the category of time, who is shooting at you and who you are with; there will be a much higher level of synergy among allies, which is not only supported by chat but also advantageous for you to play. Valorant made a similar move; they rethought and introduced, without breaking the genre, additions that slightly diversified it and made it somewhat different.

Aleksandr: We initially mentioned that after the feedback from America, there was a simplification.

Alex: The devil is in the details; don’t simplify. The version we presented had a cool nerdy tank, where you could rebuild it, and there was gameplay inside. It's more fun now, of course, but in terms of technical characteristics, it’s the same — just packaged better, so you can clearly understand that this one is stubborn, this one is fast, and the other one is something else... This is how we rethought it, but it’s practically the same, with more gameplay units in the essence you’re playing. Your unit of machine, your loadout, is more valuable; it's no longer banal, it’s yours. You choose what best reflects your play style and brings you the most enjoyment.

↑

Meet the Agents

Chapter 1

Team Structure. Key Figures

Zakhar: Can you tell us about the development team? Are there any stars?

Artem: The team currently consists of 150 people. Around 10 are based in Chicago, where they work on Modern Armor and help with consoles. There are 52 people in the Serbian office — individuals with experience working at Ubisoft and in large-scale productions, although they lack experience in releases and making complete games. For us, they are the "young blood." Then there's the core team, which survived the relocation from Minsk, comprising about 50 people, more than half of whom work in art, and 80% are former World of Tanks employees.

Among the stars is Danya Parashchyn, also known as "Murazor." He used to be a streamer, once shook hands with Viktor and criticized Rubicon as a failure. For his critique, he was told, "If you think it's bad, go and fix it." Now, he's in charge of Cold War. There are also professionals, veterans with 7–10 years of production experience, such as Misha Litvinskiy, who has always worked on hard surfaces — tanks and other vehicles.

The strongest expertise lies in the engineering department. It's important to understand that our team is building both the engine and the game simultaneously. Bronislav Sviglo oversaw the release of World of Tanks 1.0, and Denis Deshko is the system architect, while Arseny Kravchenko and Artem Brichko are tech artists. These people have been working for a long time and their superpower is making vehicles.

There are also rising stars among programmers, a group of guys who went through Forge in Minsk. Now they show their potential. Like all young people, they think more about opportunities than limitations. Ilya Yakush is one of them. Since 2020, we've also started adding people with completely different expertise to bring new perspectives. On the Game Design team since 2020, only Danila and I remain, the rest are new hires with no experience in Tanks and half of them don’t speak Russian.

You all know Hanna. For much of the team, it was unclear why she was hired as the art director for the product based on her resume. But to create a new product that stands out in the market, you need someone with her experience. The team needed to be reassembled. Deploying the old World of Tanks team wouldn’t have worked to make something fresh and new. In some departments, a third, or even half, and in some cases 80% or more of the creative team had no prior knowledge of the product.

Hanna: Some of them had never worked on games before — some came from marketing. It works well because new people bring fresh ideas. A part of them is lost, but there are the same principles of work, they know how to work under pressure, they know how to work with concepts. We manage to combine nicely because new people give new ideas. Part of the team works on metaphorical concepts, like icons, coming up with completely new approaches, free from template thinking. Everyone says we have the best-looking merch. Alex joined a little over a year ago.

↑

Don’t lose your head over your game’s challenges

Chapter 2

Team Management Challenges and Project Dynamics

Zakhar: How do you manage the internal collaboration of this big team? How do you build interactions inside the team? How do you decide which ideas to move forward with?

Artem: The preparation period could be divided into different stages, each characterized by its own methods. Right now, methods from previous periods don’t work anymore — they’ve become toxic. When we were preparing the previous builds, including alphas and betas, the team was much smaller and consequently, disciplines were smaller and the communication overhead was minimal. Since we were offline, in one room, on one floor, everything was resolved quickly. And because we were building everything from scratch, the results of each action were immediately visible, which motivated people. All it took was a quick agreement. A startup approach.

It was normal if someone in the team didn’t know what others had agreed upon — you could step in and help your colleague. I would even sit down and do things myself. Now, if I use that method, the team feels terrible because they feel responsibility has been taken away from them. This is a sign of larger-scale production and a bigger team. The dynamic is different now. What stands out is that the older team members haven’t fully adapted to the changes. Especially design, Danila and me - we haven’t adapted. Instead of doing things hands-on, we now need to learn how to delegate. Instead of thinking about how to do something, it’s more about telling someone: "Go think about it and bring me a solution." In some cases, it’s not even about setting a task but providing direction and vision.

Because we are growing from within, many things are changing. We haven’t fully defined our vision and mission. Many things happen from the ground up, which is why I still haven’t been able to explain to Nata for a year now what the conflict at the world level of the game is. One symptom of this situation is onboarding — if you were to join us now, people would tell you: "We don’t have any onboarding. Survive, and we’ll talk in six months." We didn’t even say that. We showed the product, said everything is fine and that we’re heading towards these releases. Maybe it’s not so unusual for the market anymore, as it's coming out of a crisis.

Another challenge is the team’s mindset. Part of it is used to doing things like a New Year’s feature over the course of a year. While this is changing, it's still somewhat present. They have a feeling of security in a corporation. The team doesn’t fully understand the idea of investment and the collective as a living organism. The situation is twofold: they’re building a new product, but even in case of failure, they will still be paid tomorrow. So, the team doesn’t feel responsible; it’s all on management. There’s a dichotomy: the team works with "a stable income," while the management operates like a startup, where funds are limited “daily” according to the milestones. In case of a failure the management gets fired and the team starts working on Tanks 2.

↑

Everybody’s dead and there’s a skull grinning in the middle of the screen... but I’m OK!

Chapter 3

Failures and How Management Handles Them

Zakhar: Let’s talk about tension points. Has there ever been a time when, after major investments, you had to abandon something?

Artem: Last thing that happened we had to drop the visualization of progression modules on vehicles because the production couldn’t handle it. And that was one of the product’s Unique Selling Points (USP) back in January. I expect some backlash for this. I failed to scale the production properly. This happens on a smaller scale almost every day. Because we are ambitious. Hanna has her maps, I have progression mechanics, Alex has the funnel and Nata has the world bible, a set of mechanics that deliver pieces of the world and narrative to the player.

Nata: The story is being written, but the mechanics are lagging behind. We’re constantly caught in these contradictions.

Zakhar: How do you channel this? How do you dance with what you want and what you can’t achieve?

Nata: In my case, I choose the most prominent point where I can test my hypothesis. For example, I can’t create interactive dialogues with vendors or a cool progression system in the account right now, so I take the battle VOs, which players are likely to hear, that vividly convey the story, and I test a piece of my hypothesis on them. Everything else — will be done at the right time. You focus on one standout point.

Artem: I don’t know, right now I’m not channeling this in any way. I’m in the middle of a desert where the container is overloaded and I don’t have the tools to make use of this conflict. So when the container overflows, something happens — it’s not my action, not the result of my choice. I chose not to choose. For us it’s a bad case right now. For us, there are a few recurring methods right now. One is conflict, often bigger than the actual situation. The second is to just shut up and get things done. Hanna is a good example. Just stop talking. Just take it and start doing it, show the team that this is how it’s going to be. And this strong director’s stance is a good solution right now. The third is explaining why what someone did doesn’t work. This is a cool tool. This is something that’s lacking now. I definitely lack it. To answer Zakhar’s question about how it’s being channeled...

Working on the game's appeal to players.

Barys: Are there moments when the “fun” factor in the game goes down and how do you deal with those moments?

Hanna: Going back to the question: how do you dance? We don’t dance, we run. There’s no sense in thinking about how to do something - we’re fixing things on the go. It’s hard for the team that worked on Tanks because we don’t produce a lot of finished stuff. We’re learning on the go, we make, test and fix on the go. We make a lot, throw it away and we don’t do anything perfectly on the first try. It took a long time to adjust to the idea that we don’t have the intention to make things perfect from the start. This exhausts people a lot. Now we are trying to structure. Around 80% of the work results in negative outcomes, but we have a certain flexibility in our approach.

Barys: It’s a very fine matter - fun. How do you deal with it?

Hanna: It’s a spiral. At first, something works, you dig into it, then all the fun disappears, we push again, come out on a new loop, and you ride it until it breaks again. The third iteration of Meta interface started with a background. We made a cool thing last winter, it looked cohesive, solid and strong. Then, trying new things, we broke it, but from this conflict, a new iteration was born, and by January we’ll put it back together. I see this constantly at the end of production, in design — it breaks, and finally, the structure comes together, and then it starts moving again, little by little.

Artem: The fourth thing that I forgot to add… This team has the freedom to ask for help. You are an example of that. In a very intimate matter, like naming a product. After all, the question is not how to name the product to make more money, but it’s more like: we can’t find the right wording for what we are doing, please help us.

Nata: There were moments when we made something cool, and then it went the wrong way. The same happened with the story. Initially, there was a story with the Cold War, now we have Artem as the vision holder, there’s the American team that was asked to help with cultural sensitivity, and in general, how to make our story engaging for Americans. There’s also work with you. These are the three inputs. My method is to have a check question: when you present each new iteration, how will it fit into the skeleton a year or two after launch? Will this machine keep rolling? Like a show’s engine. And then you look at the story.

PLOT CONFLICT IN THE GAME:

Zakhar: Are there any themes within the game right now that go beyond explosions? For example, the theme of conflict.

Nata: There is a synopsis. This story has a Noland flavor. Everything is very realistic, the stakes are high, but at the same time, some craziness is happening. It’s a metaphor for the Cold War, where you have superpowers and around them, smaller forces branch out. It’s a great standoff, but it’s not built on geopolitics, which we’ve moved away from, but on the conflict between man and machine. This theme is super relevant to everyone who comes into contact with a computer right now. And it will remain relevant. Besides an interesting story, there always has to be a gripping thematic discourse. The player might not realize it, but we plant it there, and for those who find it interesting, they can latch onto it. There are carriers of simple human stories — our characters, whom players can find either relatable or distant.

Zakhar: In the new version of Blitz, we thought of the concept in which characters also appear and they are communicators. You don’t play for them, play as their avatar, so the tone of voice of your game is the tone of voice of all the characters. When you realize that you have characters, each one of them appears and tells what is necessary for the audience. At this point, you have a construct: let this character tell about this update with their tone of voice, accent, music, and phrases. It’s a cool constructivist solution. There’s no Cold War, just the game, but inside, the characters already tell the story.

Nata: We’re trying to bring characters into focus, considering that in battle you don’t see them. You see the machine. In core gameplay, it’s you and the machine. Overall, yes, the tone of the characters and the tone of the game aren’t separate.

PLAYER'S FEELING IN THE GAME:

Zakhar: Do you have a sensory understanding of what players should feel when they enter the game?

Artem: For a newcomer, it’s “make a difference,” curiosity and mighty machines. For someone who has spent ten thousand hours, it’s different, but we still want to preserve that curiosity. The feeling that comes to you a second before you enter the game… The metaphor that came to me is like when there’s tension, and something is happening... like the monkey in 2001: A Space Odyssey touches the monolith — this animal has never touched a polished surface before, it doesn’t exist in nature, but it looks alluring. People have never touched such tanks, but once they do, they can’t stop.

Hanna: It’s an immersion into a strange other world and fun. You come to unwind and there’s the background of a fantasy world.

Nata: Arcade fun, the feeling that you’re welcome here, that this isn’t a game that’s too difficult. It’s fun for me, even if I’m not a super skilled player. It’s like a Caspar David Friedrich painting, where behind the figure, a vast landscape stretches out. That romantic awe of something big opening up before you — that’s the world of our game and the machines. Mighty machines. They exceed your expectations — wow, I can explore all this.

Hanna: I’d also like to add — we’re using modernist architecture. What we use in future concepts isn’t heavily present in the game yet. This curiosity when observing — that’s the aesthetic and educational part. This is my personal desire to create a cohesive, beautiful world based on modernism.

Artem: Returning to the question of channeling. Going back to the feeling of wanting to create something for people helps me get through difficult situations. I would like to have fewer personal conflicts and more creative ones. Creating some kind of entertainment focused on discovery, curiosity with the romanticism of exploration is my anchor when I move away from worries and it’s what I return to. This really helps when there are no rational judgments left.

Zakhar: When you talk about atmosphere, is there a moment when the player gets distracted because they’re drawn into the beauty of the world? Then they find their own places, slowly get to know the game, and interact with it. Or is it more about exploring the equipment — discovering new vehicles, the reason why you’re playing?

Artem: For me, it's a unified product, I am talking about this to the designers. I can’t say I feel this in the product. "I entered the location and was blown away" — I’d love to have that. The last experience I had that’s close to what you're talking about was Space Marine 2, where there’s this view in a window that made me forget I was playing a game. I wish we could grow into a team capable of creating that. Right now, our focus is on mechanics and landmarks on the map. As a team, we can only do what we can do. To make The Last of Us, the team would need to work together for 35 years and go through 10 failures.

NARRATIVE AND STORYLINE IN THE GAME:

Zakhar: We say that the game isn’t narrative, it’s multiplayer, with characters but no plot. However, a storyline often emerges that explains the world’s origins. At the same time, we talk about fantasy, geopolitics, micro conflicts and we don’t specify a geographic location. When Nata talks about conflict, how can we describe the game if there’s no plot?

Nata: You can’t say there’s no plot. There is one, and it develops. There’s a premise. And the conflict on which the world and the heroes are built continues to evolve. We have personal stories for the characters, which will develop over the seasons. There aren’t seasons yet, but they will come. We don’t live in a fantasy world, this is an alternative reality — speculative realism. We try to stay as realistic as possible. We have a world where instead of the Eastern and Western blocs, there are two rival research institutes. Each claims to be saving humanity from all possible threats. One advocates for the safe development of humanity on Earth and the other for space colonization. In reality, they were both created by the same global leaders. They compete without knowing they were born from the same force. Almost every object on the Big Dreams map belongs to one of these two powers. All conflicts are resolved through tanks, as there are rules to prevent escalating war. Force A or B hires agents who clash on the map. Plus, there’s a layer of factions, smaller organizations trying to make their own profit. In the background, there’s a looming threat to humanity, but for now, we’re not focusing too much on it. Our agents in tanks are at the center of the story. It’s a world where progress has triumphed, and global powers abandoned the atomic bomb after something very unpleasant happened during the Trinity test. Nuclear energy developed only for peaceful purposes, and our tanks became the ultimate weapon.

Barys: And how do the game's agents relate to corporations?

Nata: They are hired agents, but if you look closer, some are in it for the money, while others want to uncover who’s behind the global conspiracy. Professionally, they are mercenaries, although we don’t call them that. The dynamic is such that, through the matchmaker, you could end up working for Corporation A or B, you can’t choose. That’s why we say — our agents work wherever they’re called.

Artem: For me, the player never gets a full storyline. They receive puzzle pieces. It’s their task to assemble the pieces. But there are never enough pieces to complete the picture. An example of this is the Souls-like approach: nothing is ever clear. There are only speculations. And yet, you need to give out pieces, because stories sell.

Zakhar: The threat to humanity is the conflict. It exists, it’s existential. From this stems the existential choice: some continue to fight, some give up, some end their lives. But this all outlines the storylines to which applied stories can be attached.

Aleksandr: How strong is the Cold War connection? Yes, it was the peak of tank development, but no conflicts actually happened, and now they all have to be invented from scratch. Why doesn’t the game take place in an alternative present, and how do you justify this retrofuturism?

Artem: In the late 2010s the team was thinking about the Cold War period because the doctrine of tank combat had changed, the armor schemes had evolved and there was enough material to avoid breaking the core mechanics of World of Tanks too much and still keep tank battles and the shell vs. armor core mechanic. Because if we talk about the modern period, that mechanic no longer works. There’s a helicopter that can counter a tank and drones that destroy any equipment. Let’s repeat — we don’t have a Cold War; these are remnants of the game's creation history. Drones and helicopters exist, but they are used as abilities by the heroes.

Nata: We aren’t tied to specific years. For instance, the game has women in small shorts which doesn't correspond to any historical period, and everything is mixed from 60s pop culture to the early 2000s. It just gives the feeling that this isn’t happening now.

Artem: We draw inspiration from the aesthetics of different periods, and we’ve discarded historical accuracy as a unique selling point for Tanks.

Nata: The plot doesn’t indicate time or location. Even the buildings resemble real ones but don’t belong to any specific era. We can give some hints if needed.

Aleksandr: Is there a time limit we won’t go beyond, like walking robots, for example?

Artem: Modernity, the war in Ukraine. We need the audience’s trust that a combat vehicle can be illustrated like this in a match. There’s a subjective feeling that it’s a heavy machine, somehow tied to the military. We already have machines that don’t exist: an Abrams chassis with a railgun that’s only been developed for the navy since the 1970s, and it’s so expensive to produce that it’s not used.

The same goes for locations; there were projects for Most Driver, but nothing came of it. However, the technologies are patented or exist in other places. We leave a foundation to prevent the audience from feeling alienated. We can use a location from the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis, place a landmark there to make it believable yet strange. We can put in ships, and the audience familiar with the silhouettes of these ships will understand that it references that period. It’s pointless to talk about this because the game lacks mechanics that would support the theme of the Cold War. This is what we were told in America: you have no associations with the Cold War. No mechanics, no art, no history.

Barys: When the game is multiplayer, there isn’t much opportunity to convey puzzle pieces. Were there any thoughts on how to strategically do this? I mean beyond the game. An example is Overwatch. It’s a multiplayer game and I don’t know much about the characters’ backstories, but there are probably some titles. However, everyone knows about those Overwatch videos with character stories. I got absorbed in that topic and then I began to understand the characters’ histories. Do you have a similar strategy?

Nata: I’ll add about videos and cosmedia storytelling; I advocate for maximizing the story told in the game so that a person who hasn’t seen the videos understands the character of this game. What makes it different from similar ones? We don’t have many similar ones, but I want videos to be provided as needed so that players enter battle for a story and not on youtube.

Alex: We no longer use tank categories; we are moving beyond that. We’ve arcade-ified the gameplay — armor, guns, targeting, static gameplay. You think in different categories here. You consider where you’ll go, and who will support you; this is a different gameplay skill.

UNIQUE GAMEPLAY CHARACTERISTICS.

Zakhar: What will be the unique gameplay feature? What will I feel at my fingertips?

Barys: What must I learn to do in order to win?

Artem: You need to understand your character’s abilities to maximize them. This mindset shifts towards a more utilitarian shooter application. Finding the piano for each hero, knowing the order of each key. In our case, it’s not tanks with abilities. Speaking about Valorant I understood that this is Counterstrike with abilities. In our case this is not Tanks with abilities. Tanks with abilities are Excalibur or Still Hunter mode. Ours is like Call of Duty with tanks. We broke a lot from Current. We only kept the façade of the perception that we have armor, but the mechanics work completely differently from Current.

Aleksandr: What do you think about the term "Hero Shooter," and is it applicable to your game if you consider tanks to be the heroes?

Alex: We have another interesting assumption — when we talk about heroes, we mean a box that holds a tank, and the hero is a person, dual-faceted, which multiplies variability. The tank as a carrier of slow-paced strategic gameplay, which is more forgiving, and as a carrier of gameplay, abilities, etc. The second part is the hero as a person who gives you additional variability for reconfiguration. We’re not exactly a hero shooter; if you had the option to select abilities from different characters, then add MOBA elements with proper purchasing, where you know the order of button presses while seeing who is in front of you, whether you’re under a tower or in the woods. We’re not a hero shooter; we’re not Over. It’s not that hardcore; our base tank carries legacy: we removed armor, the three-caliber rule and some other things, but we retained the core mechanic — how you drive, how you navigate, how you position yourself and how you shoot. However, the movement pattern is different; it remains in the base and sets this vector. Therefore, in terms of sensation and perception, it’s not a hero shooter because the perception of a hero shooter is solely through a person, TPS, PPS — it doesn’t matter. Conceptually, we have a sandbox, and you think in terms of tanks, which involves knowing the locations. We also add the category of time, who is shooting at you and who you are with; there will be a much higher level of synergy among allies, which is not only supported by chat but also advantageous for you to play. Valorant made a similar move; they rethought and introduced, without breaking the genre, additions that slightly diversified it and made it somewhat different.

Aleksandr: We initially mentioned that after the feedback from America, there was a simplification.

Alex: The devil is in the details; don’t simplify. The version we presented had a cool nerdy tank, where you could rebuild it, and there was gameplay inside. It's more fun now, of course, but in terms of technical characteristics, it’s the same — just packaged better, so you can clearly understand that this one is stubborn, this one is fast, and the other one is something else... This is how we rethought it, but it’s practically the same, with more gameplay units in the essence you’re playing. Your unit of machine, your loadout, is more valuable; it's no longer banal, it’s yours. You choose what best reflects your play style and brings you the most enjoyment.